For years, property professionals have witnessed firsthand the densification of tenant spaces in the office buildings they oversee, as more and more employees occupy the same—or even less—space. In addition to dealing with the ensuing operational challenges, building owners and property managers have heard anecdotes from occupants who say their workplace is feeling too crowded. Finally, there’s some hard evidence to back up what those in commercial real estate have known for years: There’s a tipping point when what a tenant might call an "efficiently designed" office space becomes too dense—and the occupant experience suffers as a result.

Property professionals weren’t the only ones looking for the answer to the question, "How dense is too dense?" So, too, were researchers at global engineering, architecture, construction, operations and maintenance firm Jacobs. However, none of the literature they found on the topic was very quantitative, explains Ellen Bruce Keable, Associate AIA, national director of Change Management for Jacobs. So, a joint research project between BOMA International and Jacobs was born out of this need for real numbers. The results of the study come from multiple disciplines and perspectives. Keable brought the behavioral research perspective, and her fellow Jacobs researchers Lisa McGregor, national director of Planning Strategies, and Amy Manley, IIDA, national director of Workplace Performance Strategies, came at the issue through the lenses of organizational planning and performance, respectively. Data was collected through surveys of BOMA members by BOMA International’s Research Committee; insights from Jacobs’ annual Workplace Conference participants; the Jacobs Benchmarking space metrics database; and research from the faculty of the Department of Interior Design at Philadelphia University’s College of Architecture and the Built Environment.

STRESSED OUT AND MAXED OUT

"There was a time a few years ago when tenants were trying to save money by squeezing people into small spaces," Manley says. "Organizations tried to go too dense, and they ended up getting a lack of engagement because there are human limits to space reduction. Good office space design really is much more about promoting employee wellbeing and making people more engaged and productive."

This can’t be achieved when there’s overcrowding in the office space. According to the research, a sense of crowding occurs when occupants don’t have enough personal space, experience too much sensory stimulation or have a lack of control over the access of others to their workspace. Once this point is reached, tenant health, comfort and productivity can begin to suffer. So, too, can building operations, as HVAC systems become taxed, supplies in the restroom become more quickly depleted and elevators experience more wear and tear. So, what is the tipping point when it comes to density?

DEFINING THE TIPPING POINT

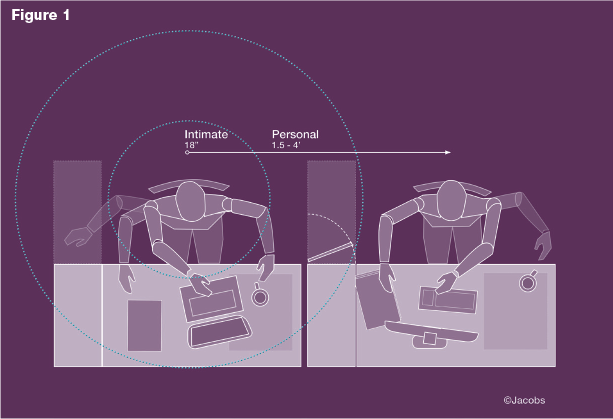

To find this point of no return, the researchers at Jacobs first started by defining minimum requirements for individual workspaces. By applying insights on the social nature of space, they came up with the minimum social distance between people to mitigate a sense of crowding—at least 4 feet of space between individuals. Realistically, in application, this means that work settings should be no smaller than 25 to 36 net square feet and at least 5 feet across to maintain adequate personal space between employees (see "Figure 1," below).

When it comes to usable square feet per workseat—which factors in meeting spaces and other common areas in the office space, in addition to individual workstations—the researchers found that 125 to 135 usable square feet per workseat is the minimum threshold in a typical corporate environment. And, organizations can’t skimp on the circulation, the areas where employees move between spaces. The denser the space, the more circulation areas become crucial "interstitial space," says Manley. "During the initial forecasting, most organizations overlook the value of circulation." As spaces become denser due to organizations trying to meet aggressive area metrics, the Jacobs team recommends dedicating at least 45 percent of the total usable square feet to circulation to allow for better space planning flexibility, variety, shape, size and configuration of work settings for a more dynamic design.

But, as the researchers were quick to point out, these are minimum guidelines. "For some organizations, there are density goals, but space realities," explains Keable. The amount of space an organization may need depends on a variety of factors, including the function of the space, workplace culture and design. "In fact, design becomes even more important as one increases density," notes Manley. "The actual space layout, the variety of available work settings, acoustics and the ability to control your own workspace all become exceedingly important." One way for tenants to achieve good design in denser spaces is to make sure their space includes an assortment of shared collaborative and common area spaces and a good mix of work settings.

FINDING THE SWEET SPOT

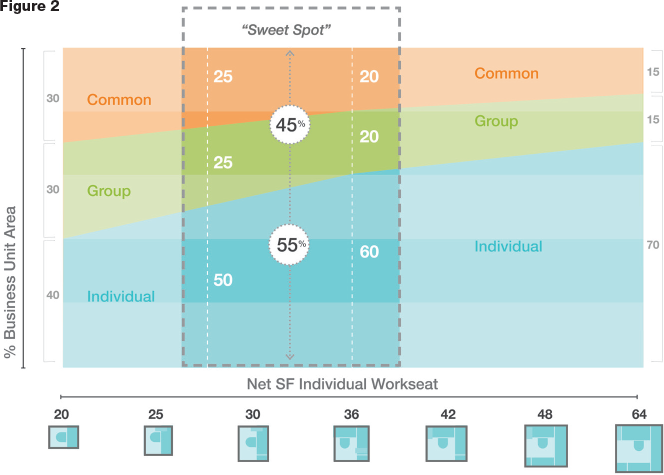

Taking the minimum requirements outlined here into account, the team at Jacobs next defined a space distribution "sweet spot" for office spaces. For workplaces with individual workseats ranging from 25 to 42 net square feet in size, this sweet spot was when approximately 55 percent of usable square feet was dedicated to individual seats and the remaining 45 percent was dedicated to group and common spaces (see "Figure 2," above). "Organizations can increase density and decrease the size of workstations if they also provide more shared and group space," says Manley.

In addition to sharing these metrics and discussing potential operational implications with tenants when they design or reconfigure their spaces, building owners and property managers also can help by augmenting the tenant experience. "They can take the pressure off the tenants by offering building amenities that become an extension of the tenant space," says Keable. This not only creates a sense of community within the property—a "vertical neighborhood"—but it also potentially can foster a connection between like-minded companies as they gather together in these building-wide spaces and share best practices.

IS THE PENDULUM SWINGING BACK?

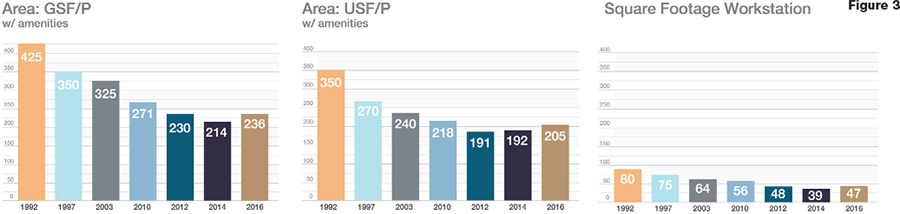

Every two years for nearly 30 years, Jacobs has collected data on space metrics as part of its benchmarking database. The researchers at Jacobs noticed that space per person was trending downwards until 2016, when the data showed a plateau in space reductions and, in some cases, even a tick back up in space allocations per person, the size of individual spaces and the number of collaborative settings (see "Figure 3," above). But, they don’t believe this is a reversal so much as a course correction on the part of tenants.

"The pendulum isn’t going to swing back all the way," says Keable. "I think density is a trend that’s here to stay for many organizations." However, what is changing is the way these organizations view the function of their spaces.

"Every person is very different when it comes to work processes—some are extroverts and work well in open space, while others truly need private spaces," explains Manley. "Organizations have realized that, in order to provide better workplaces, having a wide variety of spaces and giving employees the ability to have control and choice is very important." And, those insights might just be the first step in solving the densification dilemma.

Go to www.boma.org/densification to download the full report.

This article was originally published in the July/August 2018 issue of BOMA Magazine.