When you balance a budget, you don’t want expenditures to exceed revenue. A net-zero energy (NZE) building uses the same principle with energy—an NZE building produces or procures enough low-carbon, renewable energy to meet (or exceed) its annual consumption. This balance requires keeping energy usage as low as possible through highly efficient operations, estimating exactly how much energy will be required to operate the building over the course of the year and ensuring a steady supply of renewable energy.

Striving for energy efficiency has been a best practice in commercial real estate for decades, but creating a truly "balanced" building is a rapidly growing trend. According to the New Building Institute, a nonprofit organization working to improve the energy performance of commercial buildings, there has been a 700 percent increase in the number of buildings either verified as net-zero energy or working towards that goal since 2012. This dramatic increase is being driven by the benefits these buildings offer, including lower operating costs.

EXPANDED OPPORTUNITIES

While this growth trajectory is impressive, the majority of NZE buildings are owner-occupied properties, and one important part of the commercial real estate industry is being underserved: leased multitenant commercial buildings. Increasing market penetration of leased NZE buildings is crucial in mitigating the carbon footprint of the built environment, since commercial buildings consume much of the electricity in the United States and 52 percent of commercial buildings are leased.

The fact that there’s only a handful of leased NZE commercial buildings is due, in large part, to the split incentive issue in leased buildings—the misalignment of the capital costs for efficiency (often borne by the owner) and the cost benefits from energy savings (accrued by tenants). While NZE may make lease language more complex, making NZE a mutual goal can align the interests of tenants and building owners. With a well-designed NZE lease, the terms can be developed to give both parties confidence that this is done successfully and fairly.

Until recently, knowing what components to include in an NZE lease was difficult since few had been written, and those leases weren’t publicly available. To meet this need, Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) released its NZE Leasing Best Practice Guide. It walks through the steps of how to write and negotiate key parts of an NZE lease.

According to the guidelines, a well-designed NZE lease should include the following components:

-

An Energy Budget. Setting an energy budget for tenants in the lease helps control their energy consumption, making NZE goals more achievable. An energy budget should include the tenants’ lighting and plug loads, since those can easily be metered and are entirely within tenants’ control. While the building owner and property management team can work with tenants to determine whether heating, ventilating and air-conditioning (HVAC) and hot water heating loads should be included in their energy budget, these loads are a lot more difficult to submeter by tenant, since they tend to have central units and are mainly in the property team’s control. As a result, submetering them could add additional cost and complication.

Property managers should work with their tenants to make sure they have the tools and information they need to achieve their energy budget without impacting their productivity. The energy budget should be tracked closely, and there can be rewards and penalties in place if the budget is or is not met. An individual tenant that exceeds the energy budget can be required to purchase renewable energy certificates (RECs) to meet the NZE lease terms.

This way, even if one tenant exceeds its energy budget, the building as a whole can still achieve NZE. However, this level of granularity does require each tenant to be metered independently.

-

Disclosure of Energy. It is important for both tenants and the property team to be held accountable to their NZE goals, so tenants should receive data on how their energy consumption is tracking compared to their energy budget, as well as how the building is performing as a whole. At a minimum, a monthly report disclosing tenant-specific energy consumption and an annual report disclosing total energy consumption and on-site renewable energy production should be written into the lease. If the building is not performing as intended, tenants and the property team should work together to develop an energy management plan to align energy usage with goals.

-

Regular Recommissioning. Similar to personal vehicles, buildings require frequent tune-ups to ensure they are performing as intended. Putting a regular recommissioning requirement into the lease as an operating expense ensures that recommissioning occurs as needed and the costs are anticipated by tenants.

-

Cost-Recovery Language. For building owners to invest in energy efficiency projects or solar photovoltaics (PV), they need to recover the cost of these investments. One of the best examples of cost-recovery language is the "energy-aligned clause" created by a working group in New York, which recommends passing through a cost equal to 80 percent of the modeled energy savings for an efficiency improvement measure, so tenants have a safety factor built in if the energy-saving measure does not perform as expected.

.jpg)

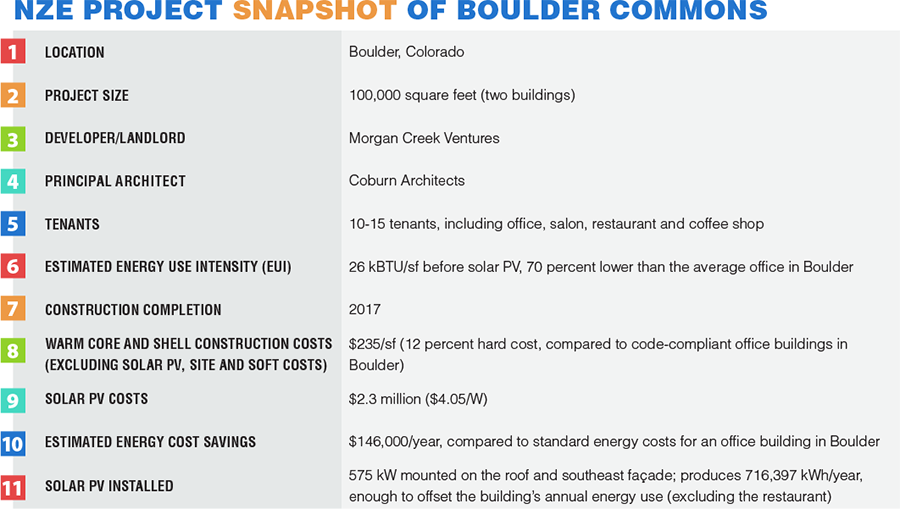

LESSONS LEARNED AT BOULDER COMMONS

Just two miles from downtown Boulder, Colorado, is Boulder Commons, home to RMI’s second Colorado office. It is the largest multitenant NZE project in the United States and among the first multitenant buildings in the country to achieve net-zero energy. This project proves that leased NZE buildings can have a compelling value proposition for the building owner, property manager and tenant—providing a replicable model for the industry to scale cost-effective and high-performance leased spaces.

Development firm and owner Morgan Creek Ventures (MCV) took a thoughtful approach to NZE from the onset of this project. Its goal was to achieve NZE with an attractive financial return, while keeping costs for its 10 to 15 tenants comparable to the local market and delivering attractive, desirable and comfortable spaces.

MCV worked with RMI and its counsel at Holland & Hart to develop a new lease structure to meet the net-zero energy goals. In order for this building to successfully achieve NZE, all tenants were required to have NZE provisions in their lease. The key NZE components of the Boulder Commons lease include the following:

-

Energy Budget. All tenants are given a plug load budget of 7 kBtu a square foot per year, 69 percent below the U.S. average office plug load usage. Tenants’ plug load energy is monitored separately, and they receive reports monthly on how their plug load usage compares to the budget. If they exceed their budget, they are responsible for paying the incremental utility bill, as well as purchasing RECs to offset their excess usage.

-

Annual Recommissioning. Base building systems are to be recommissioned annually to ensure they are operating at optimal performance. This expense will be passed through to tenants as an operating expense. The lease provides clear delineation as to what counts as recommissioning, asset improvements or standard operations and maintenance. Also, tenants who exceed their plug load budget are required to have their space recommissioned, with the cost being passed specifically to these individual tenants.

-

NZE Requirement. NZE was set as a clear goal in the lease so all parties are on the same page. If the on-site renewable energy system does not generate as much energy as the building uses (excluding the restaurant) over the course of a calendar year, the building owner is to purchase RECs to make up any shortfalls. The cost of RECs is a landlord expense, not passed through to tenants, unless the failure to achieve NZE was caused by a tenant exceeding its plug load budget, in which case it is passed through to that specific tenant.

-

Disclosure. In addition to the monthly plug load usage report, tenants will receive an annual report on the building’s energy consumption and production.

-

Cost Recovery. Since a tenant is not responsible for the utility bill, any energy improvements will directly benefit the building owner and, therefore, cost-recovery language in this NZE lease is unnecessary.

With a well-designed net-zero energy lease for a multitenant building, the terms can be developed to give both tenants and the owner confidence that this is done successfully and fairly.

Overall, this lease helps bolster an already strong business case for the developer. Boulder Commons achieved NZE at a 12 percent incremental hard cost, excluding solar PV, compared to a typical office building in Boulder. Between an anticipated 10 percent greater tenant retention and overall 5 percent higher occupancy rates, Boulder Commons will see 5 percent higher net cash flow over 10 years versus a comparable non-NZE building, without factoring in a sales premium. Additionally, when the property is sold, the anticipated half a percent lower cap rate would generate an additional $33/sf premium at the point of sale.

MOVING THE MARKET FORWARD

Boulder Commons is merely the tip of the iceberg in scaling leases that benefit owners, property managers, tenants and the environment.

"The buildings industry is notoriously an industry of followers. Nobody wants to go first," says RMI Principal Cara Carmichael. "We have gone first, and we want to share what we learned to help push the market to zero, using smart lease structures. If we can’t get our heads around a solution that’s broadly adoptable to address issues around split incentives and green leasing, then we are never going to achieve our climate objectives."

A version of RMI’s lease at Boulder Commons, the NZE Leasing Best Practice Guide and other resources are freely available on RMI’s website at www.rmi.org.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Alisa Petersen is a senior associate on Rocky Mountain Institute’s Buildings team. She specializes in analyzing paths to zero carbon performance for residential and commercial buildings.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2018 issue of BOMA Magazine.